Dear Matt,

So far in this project, I’ve endeavoured not to advocate too hard for the albums I’ve assigned you, to give you a bit more room to say your piece. I have mostly failed. This time, though, I’m throwing that whole notion to the wind because there’s no point in even trying.

There was a time in my life when I tried to purge myself of favourites. I’d say I had no favourite movie, no favourite book, no favourite composer, no favourite album. The idea was to embrace the vast and untameable diversity of stuff out there and not reduce it to a select few exemplary works. Or some bullshit like that.

Needless to say, it didn’t take. I was lying to myself the whole time: I have a favourite everything. My favourite movie is Brazil. My favourite book is At Swim-Two-Birds. My favourite composer is Mahler. And, beyond a doubt, my favourite album is Jethro Tull‘s Thick as a Brick.

People are often taken aback when I tell them that, because Tull is widely seen as a bit of a novelty act: that rock band with a flute player. But Ian Anderson’s flute playing doesn’t actually have that much to do with why I love Jethro Tull. Anderson isn’t just the guy who invented rock flute playing. He also has one of the most boundless and versatile imaginations in rock. The rest of the band is fantastic too, but they’re utterly dominated by Anderson — in a way that King Crimson, for instance, has never quite been dominated by Robert Fripp.

That’ll have to do as a primer on what Jethro Tull is, because Thick as a Brick itself requires quite a lot of explanation. The famous backstory goes like this: Tull’s major commercial breakthrough came in 1971 with ‘Aqualung,’ the title song from their fourth album. The album itself got a lot of attention, and some critics called it a concept album, because it had a couple of major lyrical themes running through it.

This was news to Anderson, who saw Aqualung as ‘just a bunch of songs.’ Moreover, concept albums were the province of prog rock, which Anderson regarded with a certain amount of suspicion. He saw Jethro Tull as an unusually adventurous blues-rock band — as different as you can get from the psychedelia-tinged pastoralism of Genesis, Yes, and early King Crimson.

So, when it came time to record the followup to Aqualung, Anderson decided to announce that difference in a characteristically outlandish way. He would produce ‘the mother of all concept albums’: a sprawling parody that would take all of the trends in progressive rock — longer and longer songs, circuitous and cod-philosophical lyrics, elaborate packaging — far beyond their logical conclusions.

The resulting album came with a satirical newspaper that took longer to produce than the actual music. It possessed a sly backstory wherein the album’s lyrics were written by a precocious (and fictional) eight-year-old named Gerald Bostock. And the record itself consisted of only one song, which spanned the entire length of the album. The fact that the technology of the time functionally prohibited this (you have to flip the record over mid-song) only adds to the absurdity of the premise.

It even manages to shoehorn a bit of elitism into the equation. The first line drips with open disdain for the listener: ‘Really don’t mind if you sit this one out.’ It would be offensive if it were serious.

But, the whole affair has ‘satire’ written all over it. Anderson has always claimed that he was basically taking the piss with this album, and that presumably spared him a great deal of vitriol when the early punks came along five years later. You seldom hear Jethro Tull cited as one of the key offenders in discussions of 70s bombast. They were just having a laugh, after all.

But here’s where that narrative falters: Thick as a Brick is the best progressive rock album ever made. It is bursting with energy, it is structurally ingenious (with almost all of the section transitions being based on the opening riff), and the lyrics are just as trenchant in their critique of England’s class system as they are in their parody of Pete Sinfield. And it’s fun. It’s just fun.

I mean, that word ‘best’ is subjective, clearly. But, among prog fans, rock fans, critics and everybody else, the idea that Thick as a Brick is in the top tier of prog masterpieces is completely uncontroversial. This, in spite of the fact that it’s ostensibly a piss-take.

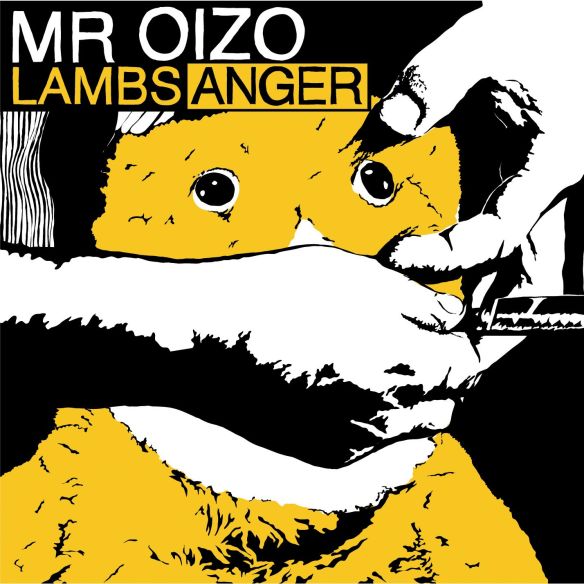

And that is why you are listening to this album at this point in our correspondence. When you described Mr. Oizo as “taking the piss out of [dance music] and its fans — while still producing outstanding examples of it,” my mind immediately jumped to Thick as a Brick.

Your experiences with Van Der Graaf Generator, Magma and King Crimson should be enough to demonstrate what prog is like in sincerity mode. So, what do you think? How much irony is there in Thick as a Brick? And do these trifling matters of authorial intent make any difference at all?

And, most importantly, do you like it?

— Matthew

P.S. I once proved that Ian Anderson is a good singer, using math. You know, just in case you’re not sure how far my loyalties extend.